As many of you know, since 2012 when I became President of the State Bar of Georgia and after a dear friend of mine, who was a Past President of the State Bar, killed himself, I made suicide prevention for Georgia Lawyers one of my causes to which I devoted my time and resources to promote. We began with “How to Save a Life,” a suicide prevention program for the Georgia State Bar, which, almost immediately, began saving lives. We reduced the stigma associated with seeking help for mental health matters, especially for lawyers. We increased the number of free mental health visits each Georgia Lawyer receives to six and with the “Use Your Six” campaign. The State Bar created the “Lawyers Living Well” program, thanks largely to the leadership of Lynn Garson, the Chairperson of the Lawyers Assistance Program. Lynn began her “Lawyers Living Well” podcast, through which she and many other wonderful Georgia Lawyers share their stories, including me. I hope you will listen. The Georgia State Bar’s Suicide Prevention Program continues under the extremely capable leadership of Judge Shondeana Morris, and many of us participated in the “Out of the Darkness” walk in Piedmont Park to raise money for the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP). I am so proud of the work the State Bar of Georgia has done, and continues to do, to reduce the suicide of Georgia Lawyers and their family members.

As part of this large effort, we have learned a lot. One thing we learned is the concept of “means restriction,” which is to eliminate the means by which someone could kill themselves when you know or suspect that person to be suicidal. This includes guns, drugs, ropes, alcohol, etc. It is important to remove any means of suicide from the surroundings of someone you believe is suicidal. Research has shown that if the means to kill oneself are eliminated and you prevent even that momentary thought of suicide, that person is not likely to resort to suicide again once the idea of it is gone and the means to do it were eliminated. As published in the medical journal Lancet, “[l]imitation of access to lethal methods used for suicide—so-called means restriction—is an important population strategy for suicide prevention. Many empirical studies have shown that such means restriction is effective. Although some individuals might seek other methods, many do not; when they do, the means chosen are less lethal and are associated with fewer deaths than when more dangerous ones are available.”

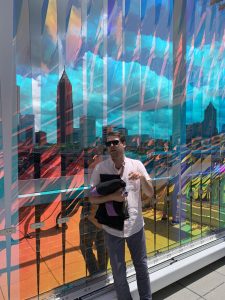

So I was thrilled to read that the long-awaited means restriction of nets under the Golden Gate Bridge have finally been installed. The effort was sparked over 20 years ago when a young man, Kevin Hines, jumped off the bridge to kill himself, but he survived. He said the second he jumped he regretted it. He said: “Had the net been there, I would have been stopped by the police and gotten the help I needed immediately and never broken my back, never shattered three vertebrae, and never been on this path I was on,” said Hines, now a suicide prevention advocate. “I’m so grateful that a small group of like-minded people never gave up on something so important.” There are other examples of means restrictions, right here in Atlanta. You may recall that I wrote about a project my son, Chastain B. Clark, collaborated on, designed, created and installed at the Georgia Tech Library called “Crosland Chroma,” which is a series of beautiful screens that allow a scenic view of the city but prevent anyone from being able to jump off the library. This photos shows the beautiful means restriction on top of the Tech Library.

Atlanta Injury Lawyer Blog

Atlanta Injury Lawyer Blog